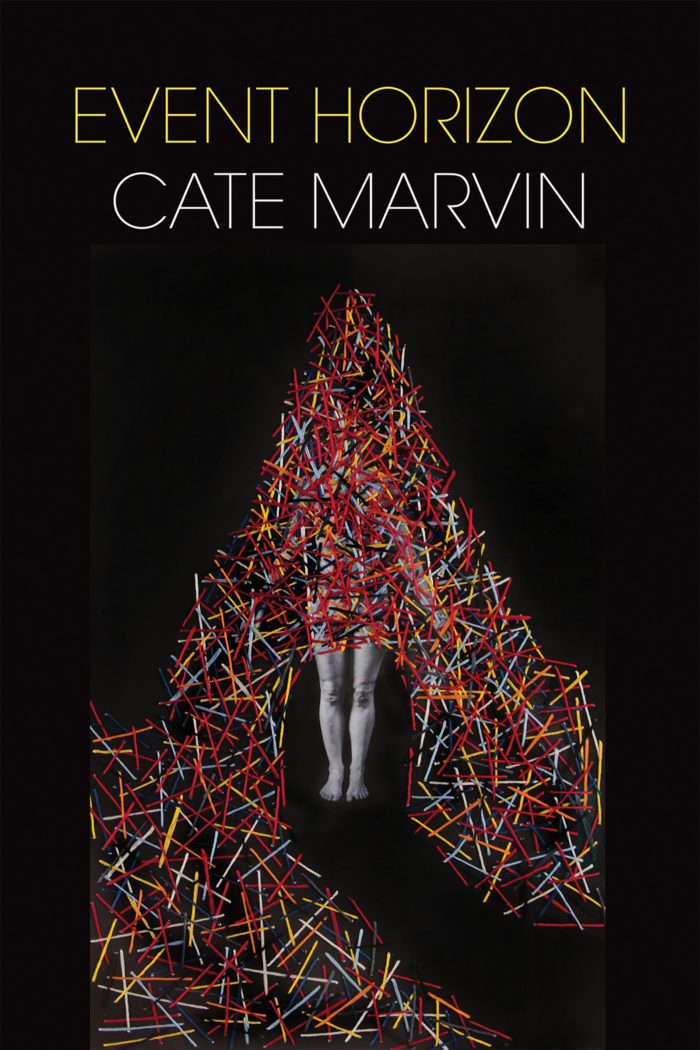

Cate Marvin’s brilliant fourth poetry collection exists just outside of calamity. Set between the violent realm of patriarchy and the bright otherworld of female agency and survival, these are poems of pointed humor and quick intellect, radical exposure and (re)vision. At Marvin’s table, the knife of domesticity becomes a threat, sharpened and shined. Misogyny pulls the sheets from the bed; motherhood wails from the backseat of the car; our hero is ghosted (abandoned, haunted) by past friends and beloveds. Event Horizon asks, at what point do we disappear into our experiences? How do we come out on the other side?

ISBN: 9781556596438

Format: Paperback

Reviews

“Sometimes Cate Marvin seems to be speaking directly to me: a poet who loves the language she loves. Her poems are made of sentient sentences. She channels the intensities of a present woman. Present being equal to nowness, witness, existence. This is simply a stunning collection.” —Terrance Hayes

“In astrophysics, the event horizon is the point at which light cannot escape the gravity of a black hole. Light and everything else appear to vanish. Cate Marvin takes the patriarchy in one hand, feminism in the other, and examines when we disappear into our own experiences. These poems blend razor wit and pointed humor into a delectable new collection.” —Book Riot

“Stunning new collection. . . . There is violence simmering underneath many of these poems. It creates tension in pieces that often concern themselves with the realm of the quotidian. . . . Recurring images of knives and broken bones continue to appear alongside instances of gardening and sunbathing or a walk around a lake. In other words, the world of these poems seems dangerous but also common.” —Adroit

“Closely observes the everyday, capturing moments we tend to walk past (or choose to forget) and drilling down to their essence, though her language remains resolutely conversational and plainspoken. . . . Many readers will appreciate the way Marvin’s bang-on honesty reframes the ordinary; an enlightening, accessible tome.” —Library Journal

“Many of these thirty-eight poems churn with the danger of being a woman in a dangerous world. The speaker itemizes her losses. She mourns a beloved mentor. A friend’s ghost visits her at a reading. Another friend has committed suicide. Her romantic relationships and flawed marriages bring turmoil. . . . And yet, as relief from the romantic turbulence, the collection is also threaded with the warmth and humor of poems about mother-daughter relationships.” —Portland Press Herald

“Marvin sets up scenarios of her past, her mother’s reactions and the ultimate concern that her mother thinks she knows her. It is a fine example of two people in a complicated relationship, a mother and a daughter who understand each other but not in the way they think they do. Mother love does that. Daughter love does that, and Marvin hits the target on this.” —North of Oxford